Table of Contents

Introduction

Social Inclusion – Physical, is an important area in the realm of accessible design. We can help people with their practical day-to-day tasks, but without social inclusion lives are lonely and isolated and can cause mental health issues. Our group focused on how physical involvement links to social inclusion and how lives can be made better with certain tools or approaches to physical spaces and across society.

Design Leaders

We each chose several diverse leaders involved with social inclusion in a physical sense, and were fortunate to conduct interviews with four of them.

Dr. Edward Lemaire is a researcher working at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. He became interested in the field of assistive technologies by way of his education. Starting from his undergraduate degree in human kinetics and biomechanics, he did graduate studies in biomechanics. Through research at what was then the Royal Ottawa Hospital, Lemaire went on to complete doctoral studies in biomedical engineering.

Henry Lowengard is an independent applications designer who has entered the world of accessibility design through Pauline Oliveros – an American composer who has developed Adapted User Musical Instrument (AUMI) with a team of composers, musicians and technicians. She invited him to create an iOS version of AUMI and it is his first project in Accessibility design. This project began with those who are not professional designers through conversations between a composer, Pauline Oliveros and an Occupational Therapist Leif Miller who wanted to know how she could include children with disabilities, in a drumming circle that she was leading. The idea was to create a non-invasive interface that would not be dependent on specialized equipment and expensive software. The AUMI software is available as a free download and the only hardware required is an ordinary computer (Macintosh or PC) with a camera.

Chantal Trudel is an industrial designer and educator. Having worked in product design, and eventually transitioning into architecture, her focus has increasingly addressed spaces related to healthcare, in particular, neo-natal care. Her background includes studies in Industrial Design and Applied Ergonomics.

Galit Shvo is a professor, industrial designer, and participant in the Reconomize group. The Reconomize group aims to affect change within municipalities, to help support local economies, and promote sharing economies. Galit works to increase inclusion within cities and economies in both her roles as a professor and within the Reconomize group. She is based in Jerusalem, Israel.

Interview Process

We collaborated on our interview questions and each contacted our designers. One was done by Skype, 2 face to face, and one by phone.

Interviews

Interview Questions

- Tell me about your projects in accessibility design.

- What philosophy of design do you lean toward?

- What steps do you take when you work on a design?

- How does your work relate to social inclusion/physically inclusive design?

- Why did you get involved with accessible/inclusive design? Why do you think it’s important?

- When did you get started in accessible design? What has changed?

- Where did you get started? Where are you now?

- What are some of the challenges in your work, for social inclusion in general?

- How do you see your work progressing?

- What is the future of your field?

- Who are key players in your area?

- Can you direct me to further information (research, papers, news articles, websites, competitors, and/or similar research in related fields)?

Context – Based On Class Work

In looking at inclusive design and ability-based design, physical access to technology and participation warranted further exploration.

Inclusive design, which addresses the widest possible audience, and ability-based design, which focuses on user ability, offer two approaches to design challenges.

However, designers still need to gather information from user environments, present it in a way that is useful, and be able to evaluate its effectiveness. Unforeseen or unintended outcomes can plague designers and users.

However, our research has led us to find that the definition of accessibility has broadened, as has the notion of disability, allowing for positive advances such as the specific application of technologies and reduction of social stigmas.

Analysis

Themes

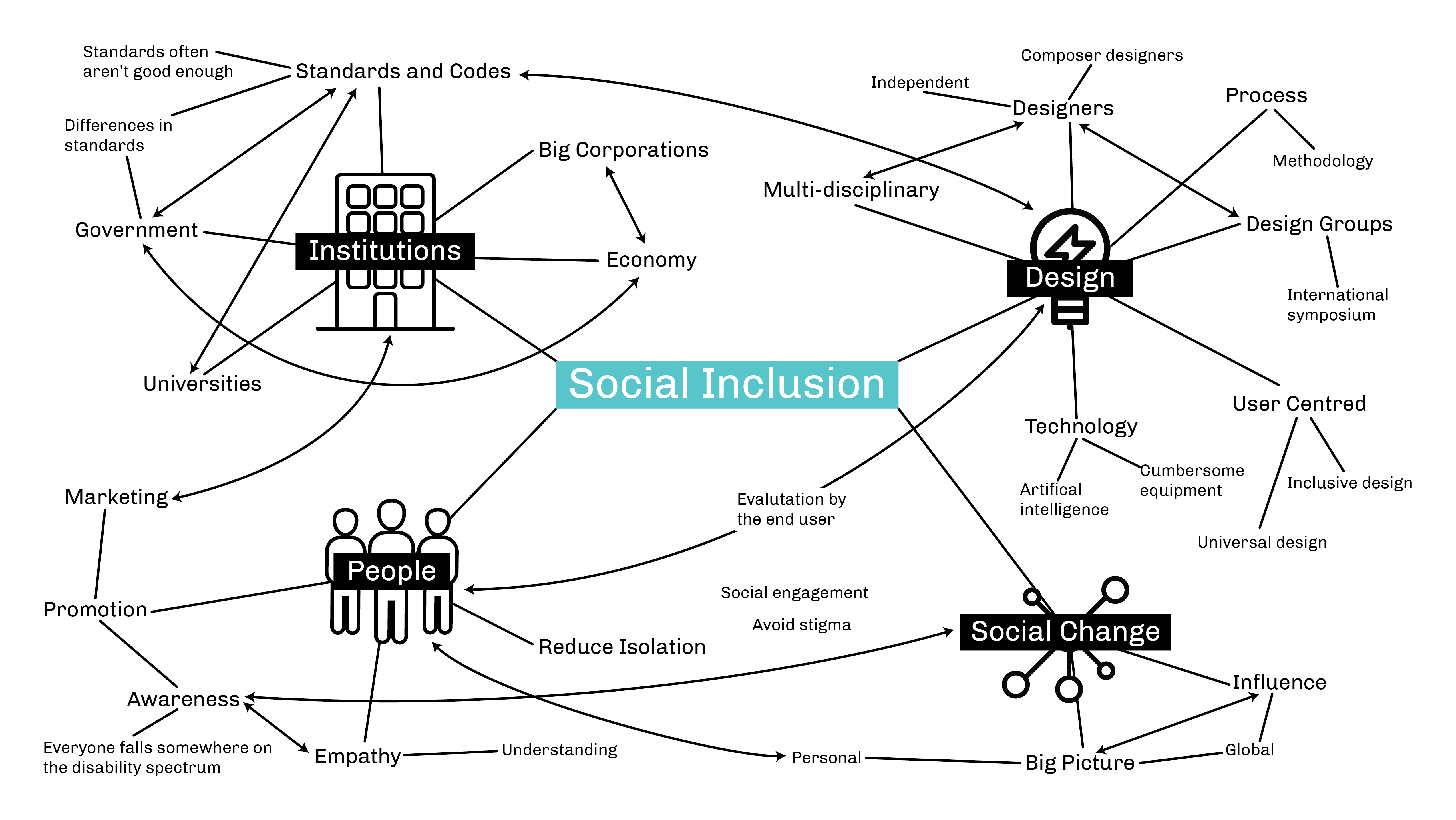

We extracted 4 overall social inclusion themes from our interviews; people, social change, design, and institutions.

People

- We found there are two groups of people who use the designs. One is the end user, and the other is the facilitator who helps the end user with successful interaction with the design.

- Our designers all found ‘people’ to be at the front and centre of their design.

- Elements of ‘People’ that were highlighted (refers to the end user)

- Reduction of social isolation,

- Empathy and Understanding

- Awareness of need, of the fact that all people fall somewhere in the ‘Ability’ spectrum.

- Avoidance of Stigma,

- Social engagement

- In all cases the designers went back to the user (often refers to the facilitator) to continue development.

Social Change

- The big picture – both global and personal

- To talk about social change, we need to talk about physical, but also emotional, social and economic, factors; none work in isolation from the other. The economy is often a force that creates inaccessibility – especially with regards to technology.

- Through social change design can change and grow.

Design

Designer Backgrounds

- One of our designers works independently

- One engages in a multidisciplinary approach

- One focuses energies on one project

- One is very interested in the overall picture of design from a global economic perspective.

- Technology

- One of our designers has created an iOS app, is very interested in Artificial Intelligence and in particular, the future use of Chatbots, Haptics, and LEAP technology.

- Design Groups

- One of our designers is involved in a collective of composers, technicians, therapists and facilitators to create the product.

- Process

- A commonality among our leaders was the process of sketching out their ideas, and coming up with a visual tool to help with development.

- All had a methodological process

- All were interested in Universal, User centred design and research technology to improve mobility.

- All were very interested in the product having a simplicity – no bells and whistles, no redundancy, nothing extra, nothing cumbersome.

Institutions

According to our leaders, institutions play a large role in design.

- Government sets the stage for setting standards and code at a Federal, provincial and municipal level. Often the code isn’t flexible enough for all people with need.

- Economy affects the development of products and if and how they get to market.

- Universities are where much of the research is done – what then? How are the products promoted and how do they gain widespread use?

- Big corporation can often set the stage for research, marketing and overall economy.

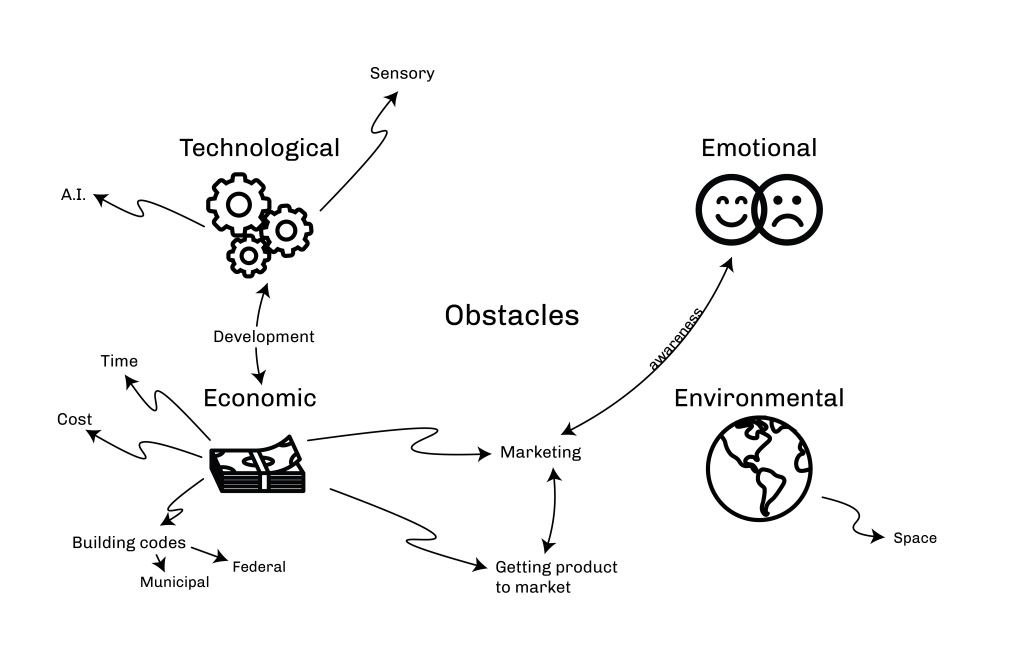

We found a thematic link with regard to obstacles. Four areas were seen to be problematic for our designers, including technology, environment, economy, and emotional.

Obstacles

Technology

- Can be complicated and this can create blocks for some people.

- Artificial intelligence will provide possibilities and possible sensory tools also, will help with advancement of accessible design and the sense we got is that there is a wait for these possibilities.

Environment

Space is often not used effectively, and such simple things as surfaces can create an obstacle. The design can be beautiful but without these simple elements in place, there is a problem.

Economy

Getting products to market, cost, time involved in creating effective products, building codes on a government level. One of our designers pointed out that we’re good at innovating in Canada, but that innovation is not often maintained here. We can speculate that the market isn’t perhaps large enough here? Or perhaps talent goes elsewhere.

Emotional

Overall awareness of the needs in accessibility needs to increase – awareness and compassion.

Overall position in terms of Accessible design

The overall position is that universal design, user centred design, and simplicity are the key to good accessible design.

A Deeper Question

Our leaders interest and concern for individuality, awareness and compassion led us to discuss that people should not be labelled according to their challenges. Even saying ‘challenges’ too general, as many people with what we perceive as challenges, do not themselves see it that way. People with disabilities come from a diverse background. One ‘disorder’ does not encapsulate the needs of people with that disorder. A person with Cerebral Palsy for example, could be anything from fully functional in the world on a cognitive level, to fully dependent. A person who is blind may not see blindness as a challenge but as a blessing in their life.

Video link to footage from the 2017 Research and Education in Accessibility, Design, and Innovation (READi) Symposium at Carleton University

00:00 – Introduction by Matthias Neufang, Dean, Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs

04:15 – Remarks by Yazmine Laroche, Associate Deputy Minister, Transport, Infrastructure and Communities

10:30 – Keynote by Alfred Spencer, Director of the Outreach and Strategic Initiatives Branch at the Accessibility Directorate of Ontario (ADO)

38:45 – Closing Remarks by QJ Zhang, Associate Dean, Research, Faculty of Engineering and Design

42:55 – Questions and Answers with speakers

References

Finch, M., LeMessurier Quinn, S.,and Waterman, E. (2016) Improvisation, Adaptability and Collaboration: Using AUMI in Community Music Therapy. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, 16(3). Retrieved from https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/834

Doi:10 15845/voices.v16i3.834

Howcroft, J., Kofman, J., and Lemaire, E. D. (2013). Review of fall risk assessment in geriatric populations using inertial sensors. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 10(1), 91-91. doi:10.1186/1743-0003-10-91

Howcroft, J., Lemaire, E., Kofman, J., and McIlroy, W. (2017). Elderly fall risk prediction using static posturography. Plos One, 12(2), e0172398. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172398

Howcroft, J., Lemaire, E., and Kofman, J. (2016). Wearable-sensor-based classification models of faller status in older adults. Plos One, 11(4), e0153240. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153240

Hunt, A. and Kirk, R. (1997). Technology and Music: Incompatible Subjects? British Journal ofMusic Education, 14(2), 151-161.

Lemaire, E., Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. External Research Program, and Canadian Electronic Library (Firm). (2010). Effect of snow and ice on exterior ramp navigation by wheelchair users: Final report for canada mortgage and housing external research program. Ottawa, Ont.: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Knox, R., Lamont, A., Chau, T., Hamdani, Y., Schwellnus, H., Eaton, C., Tam, C., and Johnson, P. (2005). Movement-to-music: Designing and implementing a virtual music instrument for young people with physical disabilities. International Journal of Community Music. R(1).

Retrieved from http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/MediaManager/Archive/IJCM/Volume%20B/06%20Knox%20et%20al.pdf

Lem, A., and Paine, G. (2011). Dynamic sonification as a free music improvisation tool for physically disable adults. Music and Medicine. 3(3), 182-188

doi: 10.1177/1943862111401032

Magee, W.L., andBurland, K. (2008). An exploratory study of the use of electronic music technologies in clinical Music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(2), 124-141.

doi: 10.1080/08098130809478204

Minevich, P., Waterman, E., eds. (2013). Send and Receive: Technology, Embodiment and the Social in Sound Art, for The Art of Immersive Soundscapes. Anthology and DVD. University of Regina Press: Regina.

Nagler, J. (1998). Digital Music Technology in Music Therapy Practice. In C. Tomaino (Ed.), Clinical Applications of Music in Neurologic Rehabilitation, (pp. 41-49). Saint Louis: MMB

Oliveros, P. (2005). Deep Listening: A composers sound practice. New York: Universe inc.

Oliveros, P., Miller,L, Heyen, J., Siddal, G., Hazard, S. (2011). A musical improvisation interface for people with severe physical disabilities. Music and Medicine 3(3), 172-181.

doi: 10.1177/1943862111411924

Story, M.F. (1998). Maximizing usability: The principles of universal design. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal of RESNA, 10(1), 4-12

doi: 10.1080/10400435.1998.10131955

Trudel, C., Cobb, S., Momtahan, K., Brintnell, J., and Mitchell, A. (2016). Developing tacit knowledge of complex systems: The value of early empirical inquiry in healthcare design.Technology Innovation Management Review, 6(9), 28-38.

Tucker, S., Oliveros, P., Rolnick, N., Sun Kim, C. Tomaz, C. Whalen, D., Miller, L., Heyen, J. (2016) Stretched boundaries: Improvising across abilities. In G. Siddall and E. Waterman (Eds.), Negotiated moments: Improvisation, sound and subjectivity (pp 181-200). Durham, NC: Duke University Press doi: 10.1215/9780822374497-011